“The Park isn’t the same as it used to be.”

It turns out this first line of Chapter 8, “Practicing Eternity”, in Lucy’s Way is hitting me in new ways these days.

When I originally wrote “Practicing Eternity”, it was Chapter 9, and it was a whole lot different, but that first line was the same. With my first draft weighing in at more than 105,000 words, I knew I needed to make cuts, and I was challenged to do this by my editor, D. Patrick Miller, who also became my assisted publisher.

One of the tough edits was nearly eliminating an entire chapter devoted to my father. It was a great testament to him, but at the end of the day I made the realization that while it was a great standalone chapter, it didn’t move the narrative of Lucy’s story and impact on me forward. It didn’t have enough to do with Lucy, and let’s face it, this is HER story.

The magical part of the editing process was combining the original chapter 9 and Chapter 10, titled “So Long”, which was the chapter about my dad. And in the end, I think “Practicing Eternity” is one of the strongest chapters in the book, unfolding exactly as it was supposed to, capturing the essence of my father in this concept of practicing eternity.

It was a difficult change at first, but one I rolled with. And in honor of my Saluke family reunion at Pokagon State Park this weekend, I’m resurrecting the “So Long” chapter from the cutting room floor and including it at the end of this blog. Warning: do not read it unless you like any of the following: summer, baseball, fun and joyful family stories, Lucy, The Karate Kid…oh, the list goes on.

But first, another lesson in rolling with change.

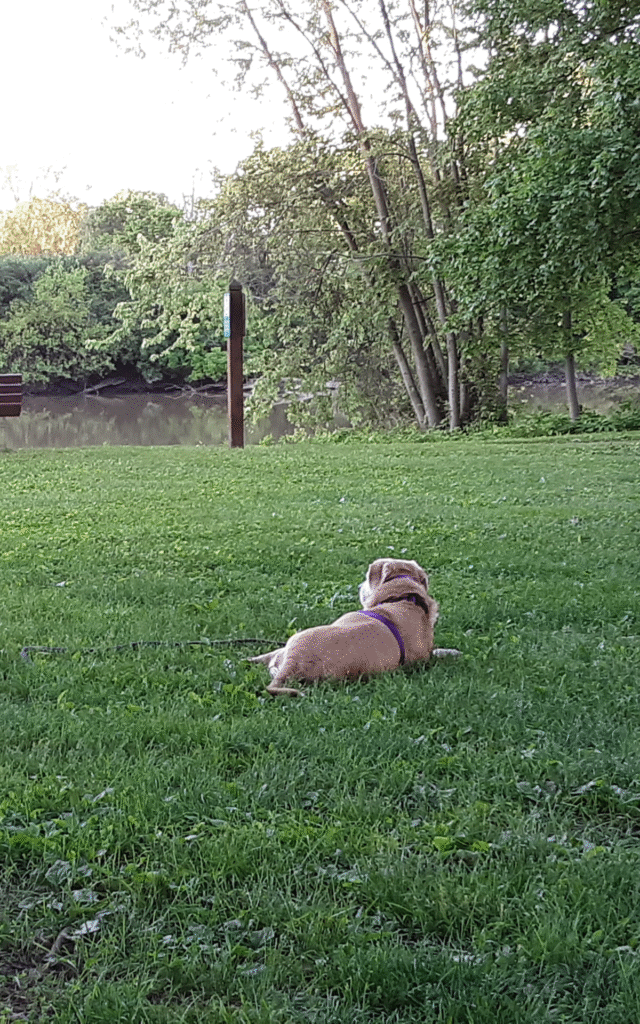

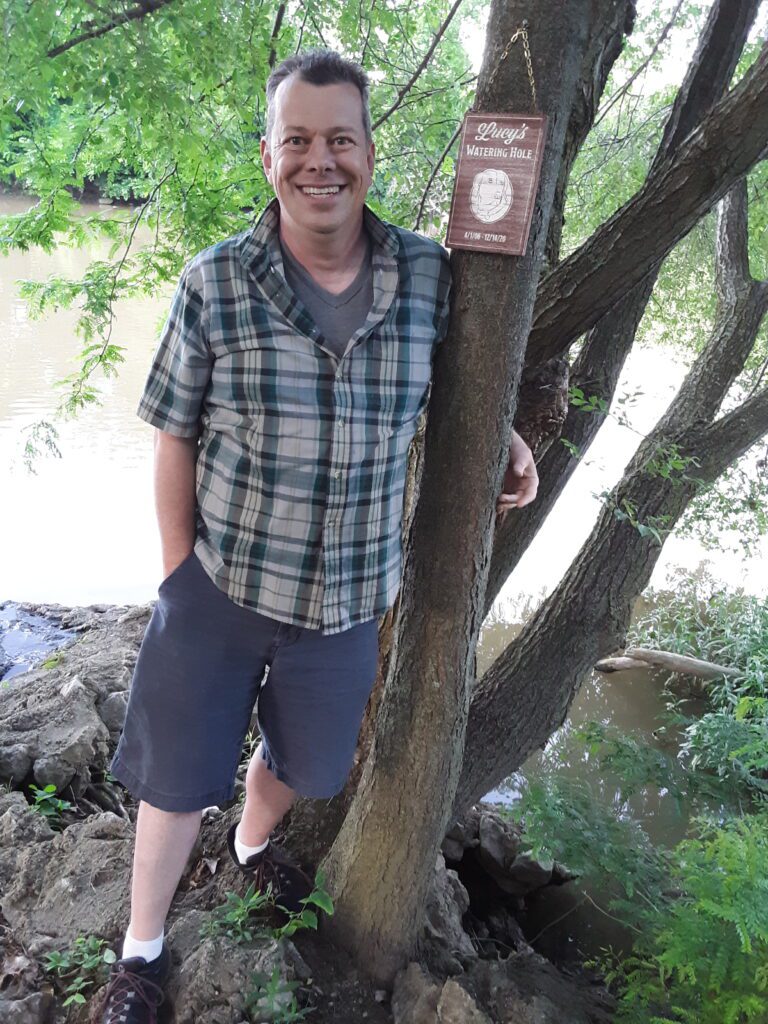

If you’ve read at least part of Lucy’s Way, then you’re aware that the little park down at the Mississinewa River next to a red girl scout cabin holds a lot of weight in my heart. It lives and breathes on several pages of the book. And for the better part of four years, I made the walk down the alley and over to that park, the one Lucy trained me to take, entrancing myself in new forms of walking and river meditation as I made my way to that little spot by the storm outfall at the edge of the water. I even hung a plaque on one of the trees, commemorating that spot as “Lucy’s Watering Hole.”

And then this happened…

A broken tibia, fibula, and a fracture on each side of my ankle thanks to a slip on the ice. My New Year’s Eve surgery began eight weeks of non-weight bearing, and some big lessons in slowing down and dealing with change.

By the time March rolled into April, I was back on two feet, but still not able to make those walks. So I’d drive over to the park, park at the girl scout cabin as I often did with Lucy, and walk over to that storm outfall, remembering the joys I’d known in this park, rubbing my hand over Lucy’s plaque and the tree where it hung. Then I would head over to the bench at the playground area and sit in meditation for a bit, soaking in all of the beauty of nature all around.

At the end of May, it was time for my hardware to come out, and one plate and 11 screws lighter, I was back on two feet by the beginning of July, much quicker this time around. With life getting busy with Lucy’s Way events, I didn’t make it back to the park until mid-July. When I’d drive by, I could definitely see the park wasn’t the same as it used to be. Then, a few days before my July 19 book talk and signing at the Marion Public Library, which turned out to be a humbling success in many ways, I made it over to the park, to this…

Making way for a splash pad. My internal dialogue battled with the lyrics of a song, something along the lines of paving paradise to put up a parking lot. But then, I thought about what this splash pad could do for the community. I thought about the underprivileged children whose families can’t afford trips to beaches and the local waterpark, and I pictured those children having the opportunity to enjoy this.

And then I saw this…

It was at this point, my internal, non-meditative dialogue revved up again, as I pictured an important city suit in a hard hat cutting down my Lucy memorial in the name of progress, throwing it in a dumpster, all in the name of not fitting the city image and brand or some such nonsense.

I already had the first paragraph of my letter to the mayor written in my head when I came to my senses and figured any complaints would probably earn a return complaint that I defaced city property by hanging this tribute.

A few days later, at the library reading, as I chose to read from Chapter 8, beginning with that first line, it hit a different way.

“The park isn’t the same as it used to be.”

You better believe it’s not. And that’s okay. Because the memories of what that little park used to be, and what it meant to me, are cemented into the pages of Lucy’s Way.

Just like I did with my edit of this book, I need to continue remembering that change is a definite, and Lucy taught me how to roll with it.

Here’s hoping you enjoy “So Long.”

10- So Long

In 1984, I became a lifelong Chicago Cubs baseball fan.

That summer was my first trip to Wrigley Field. I can’t say I remember the ambiance of the field, the surroundings, or anything more than bits and pieces of the day. I remember my favorite player, catcher Jody Davis, hitting a home run. And I remember, with just a little help from the internet, that Rick Sutcliffe pitched a complete-game shutout over the St. Louis Cardinals in a 5-0 Cubs win.

What I remember since then is too many losing seasons to count. Too many disappointments. Too many hours spent claiming my days as a Cubs fan were over. Only to go back.

But that first trip to Wrigley was magical. It opened the door to collecting baseball cards, and playing youth baseball. Living out the dream of covering and writing about baseball as a sports writer paid homage to that fateful day in the summer of ’84.

That autumn, just before I turned eight years old, I went to the movie theater and saw The Karate Kid.

The movie resonated with me as a feel-good story of an underdog overcoming bullies. I would know my own bullies – name calling, making fun of me and forcing me to stand in a corner when I was shy, laughing at me not knowing how to swim, threatening to beat me senseless if I didn’t sneak candy out of the porcelain clown cookie jar at home to take to them – but I knew many more friendships than I did these woes growing up.

Over the years, the movie grew on me as the tale of a teenager finding solace in an unlikely father figure. As I grew older and began a life in recovery, the lessons of seeking balance and remaining focused seemed to go hand in hand with the lessons I was learning in sobriety. I was also drawn to the music of the movie. The timeless Eastern score, set to cavernous and echoing melodies centered around pan pipes and wooden flutes, calling to mind ancient Asian culture, tranquility and peace, balanced with an ‘80s soundtrack cementing it to a specific timeframe.

The Chicago Cubs and The Karate Kid remain two of my favorite things, and there’s good reason for that.

All these years later, whether I’m trekking up to Wrigley Field or getting lost again in the opening score and credits of that movie, every time calls to mind the memory of experiencing each of these things for the first time with my father.

*****

On my bookshelf are two books that changed my life and strengthened the bond I was building with Lucy in those years I was living with her at my parents’ home.

As an English and journalism major, I read a lot of books, keeping several of them in an attempt at building a small library over the years. After graduating college, in the throes of my budding alcoholism, I took a job at a bookstore in the local mall. This led to even more opportunities to read as well as build an ever-expanding library that grew to comprise four three-shelf book cases at one point, which was expansive in my world. I can’t say that all of those books, or even a few of them, changed my life.

But two did.

With Lucy and I firmly established as best buds and me accepting the role of her dad, I fell into the world of dog literature at some point in 2009 when my sister Laurie lent me a copy of John Grogan’s Marley & Me that I’ve never returned.

A book had never brought me to tears until I finished this one, sobbing like an eight-week old baby as I finished the final lines. The reasoning was simple. Had I read it before Lucy and I had grown into this bond of a boy and his dog and a dog and her boy, it wouldn’t have hit the same.

But things were different.

Sure, Grogan’s memoir of he and his dog was a fantastic read, a well-written, heart-wrenching gut punch, but having a dog in my life who had become my best friend lent a stronger emotional charge.

Even though I looked over at her that day, tears streaming down my cheeks, and she returned my emotional outpouring with a stoic stare before turning her head away from this annoyance and laying her head back down, I’d like to think we both knew things were evolving. Here Lucy was, three years old, and I was already being hit with the first pangs that, one day, we were going to have to say goodbye.

*****

My cousin Bill dropped off a few letters a while back that my dad had written to his oldest brother, my uncle Bill, and his family during his final winter in Korea in 1952.

They were simple stories of holidays and daily work routines, scrawled in a neat, tight cursive font.

He was eloquent when he wrote, though not wordy. He would leave that craft to his son. He was very simplistic. I remember one of his specific phrases that he would often say in his later years: “Whatever will be, will be.”

It took me several years to realize how Tao this statement was. How Tao my dad was.

Doing nothing and leaving nothing undone. Knowing by not knowing.

Much like Stephen Mitchell’s translation of the 10th verse of the Tao Te Ching:

Giving birth and nourishing,

having without possessing,

acting with no expectations,

leading and not trying to control:

this is the supreme virtue.

My dad didn’t say a lot about his time in Korea, but the stories I heard were enough for me to know it wasn’t always what was expressed in those letters. He told me once that his first Christmas, that far away from home, he felt a loneliness like nothing he had ever known.

My uncle Jon on my mom’s side once told me a story my dad shared with him, of how he had sought solace in a priest in Korea to talk about how homesick he was, how the things he was seeing and doing was taking a toll. That priest pointed him to a bottle of booze. He said that would help him get through. The priest said there would be plenty of it anytime he wanted.

Reading those letters, he talked about how he knew he would be coming home sometime that following year. He was glad to have served his time.

I smiled at the way he signed off in those letters: “So long, Love Don.”

To me, it just seemed like a cool, simple way for a young man in the early ‘50s to say farewell in a letter.

It was the end of 1952 when he wrote those letters, and he would be home in 1953, marrying my mother a few years later in 1955.

*****

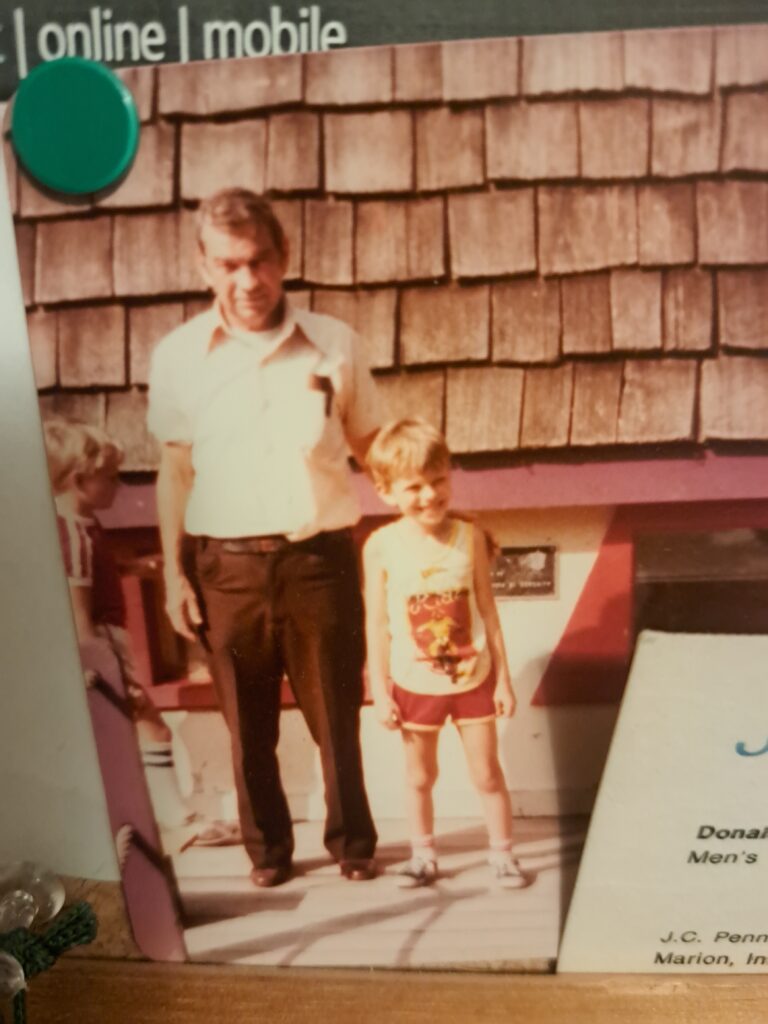

My earliest memory of that spot along the river where I spent so many moments with Lucy over the years was when I was very young, maybe four or five years old.

The memory is blurred and discolored, but it’s there. The water was low enough that a peninsula stretched to the middle of the river, and I edged cautiously and curiously along the narrow strip of land to reach the larger center. My father beside me, I bent down on my hands and knees, digging into the wet sand and scooping out several large clam shells, some of which are still packed away somewhere in my apartment.

My earliest memory on that river was also one of the earliest memories of my father.

Back in the now, today, June 20, 2021, it’s my first Father’s Day without Lucy. I see pets as our children, and I always said that Lucy was my daughter. I cared for her the same way a father would care for a young child, overprotective and trying to shelter her from the pain of the world.

When I failed her, whether real or perceived, remorse and regret twisted and twined like vines through my head. Seeing her in varying states of bliss – sunbathing in the grass, adventuring into a wooded or mucky area off the beaten path, exploring life and all of the beauty that it has to offer – left a warmth resonating from deep inside that moved through me like warm sunshine, up my arms and down my legs.

Eventually, Lucy agreed to share me when Zoe came around.

I’d known Wende’s daughter for years before, but Zoe was 16 when Wende and I started dating and our paths intertwined in a different way, welcoming her into my life as if she had always been my daughter. Zoe’s biological father was absent much of her life, so we figured out the father-daughter thing together.

And her text this Father’s Day morning reminded me that even though Lucy is gone, I’m still pretty good at the father thing.

In two days, zoe, her fiancé Todd and Wende will join me when I hang my Father’s Day present, a small piece of wood measuring six inches by eight inches, stained dark and attached with a chain at the top to hang on or over a limb, in this spot. It will read Lucy’s Watering Hole with an image of her taken from a cross stitch my friend Kelly made for me and the dates 4/1/06-12/14/20.

As I look back over the years, I’ve tried to be a presence of light in Zoe’s life, someone she could turn to and talk to, someone who tries to be involved in both her joys and sorrows, while also keeping a distance that allows her to make her own successes and mistakes, not attempting to live her life for her.

I don’t interject myself and offer my opinion unless she asks, and I try to live my life in a way that she sees the positive energy that I carry into my days while still having the ability to laugh at ourselves and the strange things around us.

I guess I try to treat her much the same way I was treated by someone else growing up.

*****

I think it’s easy for me to put myself into Lucy’s shoes, or paws, rather, when it comes to thinking of how much she thought of my dad.

If I were to try, I would probably think that she saw a comforting body to nap with through the afternoons, an old soul that held a calming presence throughout the day to counter all of the excitement and walks and animated conversations and frolicking of her dad, a giver of scratches behind the ears, and a provider of companionship.

Oh, and the food! We can’t forget about the food.

Lucy got to a point where she could sense my dad’s locations in the house and the two spots where he was most likely grabbing a snack in the middle of the day and proceed to meet him there based on the pace of his steps before he’d even had the chance to alert her with the refrigerator door swinging wide or a crinkling bag rustling open.

At times, I tried to put an end to the snacking with firm restrictions brought down on both of them. They would both look at me like punished children, and then eventually my watchful eye would loosen and they’d be right back at it again.

Before I knew it, I had a lunchmeat connoisseur on my hands.

My dad would spend several minutes tearing up food into small pieces to give to Lucy when she would likely have preferred to just snatch it out of his hand whole, like a wild beast with no refinement. My dad went through this same ritual with our dog Pepper several years earlier, tearing lunch meat into tiny little shards to give to him.

It took me a long time to realize that what he was doing really had nothing to do with the food.

Slowing down is often what it takes to fully enjoy and appreciate the moments of life as we get older. My dad was making the most of his moments with Lucy, giving her a nice, long goodbye.

Lucy never got to the point where she stopped eating her nourishing food, and while she would peak at 70 pounds in 2013, she was never that heavy based upon people food from Grandpa Don.

Because at that age, Lucy was spry and agile; our walks would often leave us both huffing and puffing, but hers was more out of joy while mine stemmed from exhaustion. And she would grab hydration along the way from any water source she could find aside from the few that I would not allow that seemed to smell as if something deceased would rise to the top at any moment, or when the muck was more prevalent than the liquid content.

In those days, if we would get to a spot where I felt safe to unleash her in a stretch of field she would start her famed lap running, which consisted of her sprinting to some particular point, turning on a dime with a precision cut, and sprinting back towards me, only to make another precision turn right before meeting me and repeat the process until she’d had enough.

Watching her run and play like that was a true thing of beauty, and my heart brimmed so full of love that I felt as if I couldn’t hold anymore, watching this beautiful creature without a care in the world, completely at one with the universe.

She also enjoyed running like this when she was still leashed, dragging me along for the ride, me giving off the impression of a dancing noodle silhouetted against the sky.

People would often look at us dismissively, or even with a roll of the eyes. We were the unkempt and untrained combo compared to the refined dog walkers and owners we’d come across.

What I do know is that Lucy and I were in the best shape of our lives in those days.

And at the end of those adventures, Lucy would find Grandpa Don when we returned home, haggling him for a bit of a nibble and then drifting off to sleep for a bit by his side.

*****

The other book I read during this time that would greatly affect me was Bruce Cameron’s A Dog’s Purpose. While this was a fiction book, it hit in the same way as Marley & Me. This time, I found myself tearing up from the start and at times bawling uncontrollably as I read it.

On my way out of the library one day in 2010, picking it up and giving it a scan on my way out and deciding to check it out on a whim.

When I picked up a copy of it at a Goodwill store in 2021 and started flipping through the pages I immediately started to tear up again, though this time it was in the middle of an aisle in Goodwill rather than in the privacy of my own home. I purchased the book, and today it’s squeezed in next to Marley & Me on the bookshelf. I was affected in much the same way when watching the movies.

To see the world through the eyes of a dog was both entertaining and awe-inspiring. And with a theme revolving around reincarnation and a dog living through several lives on the way to discovering his ultimate purpose left me feeling mystified at the realm of possibility and truth to such a thing. The book gave me a renewed outlook on humanity, and strengthened my belief that Lucy was in my life and I in hers for a very specific purpose.

I had to face the fact, while she wasn’t my biological daughter, I was in fact a father.

A Dog’s Purpose further solidified my love of Lucy, my love of animals. It strengthened my growing belief in the bond between this dog and me, that she was this living and breathing entity that knew pain and joy just as humans. It furthered my belief that I wanted to give her the best life that I possibly could.

From there, I read a pair of Dean Koontz books that involved his dog Trixie. One of these was actually “written” by Trixie, titled Trixie’s Guide to a Happy Life, and the other was a memoir written after she had passed.

Again, these books allowed my love of Lucy to grow even stronger, allowed me to begin seeing life through the eyes of our four-legged friends, the way they live simply, love unconditionally and play joyfully. If humans could only live that way, I’d contemplate, before quickly shutting down that wild notion. I can’t change humans; I can only change me. So I began to strive for these things in my life.

I continue to work on those simple lessons from Lucy today.

I appreciated Lucy more and more with each passing day. I appreciated her companionship, the sound of her sleeping, her unwavering loyalty to me, the growth into a beautiful, strong and healthy dog. I had helped her along in her journey by doing the right things. I had started taking her to the vet regularly, being a responsible dad.

I remember a lot of things from those days. Visiting with my dad as Lucy would nap beside us, or taking turns bringing a toy up to one of us, my dad trying but usually unable to get the toy from her vice grip jaw. Or catching Lucy and my dad in the middle of one of their not-so secret snack routines.

I remember that the afternoons seemed to stretch into beautiful eternity.

I remember going down to the porch on Christmas Eve and seeing blood spattered across the wood. When I came back upstairs, a blood-soaked rag in the kitchen. My dad had slipped and fallen on the porch when he went down for the morning paper. He said he was okay, asked me to please not tell mom it had happened.

I remember less than a week later, on December 30, 2010, coming home from a walk with Lucy late that morning to find my dad sprawled across the living room floor. He had fallen and broken his hip.

Everything changed with that fall that day. That was the beginning of the end for my dad.

*****

My parents were married for more than 55 years. They celebrated their 55th wedding anniversary in September of 2010, just a few months before my dad fell and broke his hip.

Nearly five months passed between that day and his passing. Aside from one short stint home for a few days, those weeks and months were spent back and forth between the hospital and nursing home, a blur of hallways and rooms and lounges and doctors and nurses that I think would still confuse me and seem lightning fast even if it were playing back in slow motion. I was with him for most of that time, and those were some of the most difficult moments of my life.

I was a shield, seeing things so my family didn’t have to see them, having conversations with countless nurses, doctors and surgeons so my family didn’t need to have them.

My recovery actually grew stronger in those days. One of my sisters would often relieve me in the afternoon and I would go home to tend to Lucy.

In the evenings, my mother would come by after work and I would seek out sober circles of friends to spend time with. I would not even remember what was said or what I said on many of those evenings with those groups of friends, but I would regain enough strength to go back that night for a few hours so my mom could go home and get ready for bed, and I would return home to Lucy and my mother at night and get ready to do it again the following day.

I would take Lucy to see him some days in the nursing home. He had a suite which gave us privacy, but Lucy had picked up a penchant in those days for barking at anything and everything and she made a lot of noise.

She would also get so excited to see my dad that she would jump up onto the bed and onto him, which was usually not a good thing following all of the surgeries he’d had. It was confusing to her as she couldn’t get next to her Grandpa Don the way she once had. She eventually stopped trying to get up into the bed with him.

Only working part time myself, I saw this as the best possible scenario for me to be there for my dad as much as I possibly could.

It was also a chance to continue working full time on myself.

Different recovery circles call it different things – sponsor, mentor, recovery coach, counselor – the name doesn’t really matter. What matters is that I had found someone who had helped guide me in those early days of sobriety, and as part of my ongoing journey, I was trying to give that back now.

The percentage of people sticking around in recovery for the long haul is small, and that’s an unfortunate problem that continues. But I was very blessed at this time with several men who reached out to me regularly seeking guidance in their early journeys of recovery. Several of them called me often. Two in particular, Carroll and John, called me nearly every day, sometimes several times a day.

I’ll never forget something that my friend Don, the man who helped me so much early in my journey of sobriety once said to me: “Believe it or not, you’re helping me more than I’m helping you.”

I didn’t used to get that, but now I did. Talking to all of those men on a regular basis, especially Carroll and John, let me know that others were thinking of me, but also got me out of myself.

And during those difficult days, Lucy was always waiting patiently at home, providing a sense of comfort and serenity when I would return. I know that I didn’t give her the full attention she deserved in those months, but she just seemed to understand that I had to take care of Grandpa Don. And she continued to be there for me.

It was a perfect balance, recovery and Lucy, keeping me in harmony and sane during those trying times.

Things became a blur at times between the nursing home and hospital visits. But one of the things I remember quite clearly is a particular bathroom in the hospital, tucked away at the back of a lounge next to the critical care department. I went in there on more than one occasion to break down and cry when I had been told that there was nothing else that could be done for my dad and that he might not make it through the day. Yes, that is something I was told more than once.

On the day of my father’s passing, I remember crying in that bathroom once again before I made difficult calls to my mother and sisters that morning. The doctors had said once again that they had done all they could and there was nothing more that could be done.

I made those phone calls to tell my mother and sisters that this really did look like the end, and that we should settle in for the final haul.

I went home to take care of Lucy, feed her and walk her. There was no more crying that day as I had no tears left. She had known that things were different for a while now, but she was a trooper. She took it in stride, making the most of the short time we had together. She probably just chalked it up to getting extra rest before going into overtime working to take care of her dad and Grandma Ann.

With the hospital just a few blocks away, I had spent most of my waking hours with my dad those past several days. When I was at the park walking Lucy and got the call from my mom that he had passed, there was a sense in her voice that I had not been there. But I had been there all the days leading up to it. We had been saying goodbye for the past five months.

At my father’s viewing, I did my best to fight back tears at the outpouring of support from the recovery community. Among the first to arrive were Don, Carroll and John. I talked with them briefly before the influx of traffic began. I looked up at one point and noticed John and Carroll still there, at the back of the room, just the two of them standing together. Hours later, when it was all said and done, they were still standing there, and were among the last to leave. The following day, they showed up for the funeral as well. It was humbling beyond words to think that less than four years earlier, I was drinking myself into an early grave. Today, these two men who I was simply trying to help guide to a better way of life were standing by my side through one of the most difficult moments of my life, giving back to me so much more than I felt I had ever given to them.

John and Carroll had stood right there by me as I said my final farewell to my father. Carroll would later tell my uncle Jon in private that I had saved his life.

*****

One of my favorite pieces I’ve ever written was a Father’s Day column about my dad and baseball.

The column was actually about much more than what it seemed on the outside, of how my father opened the door to my love of baseball, and of the Chicago Cubs.

It focused on how those memories together helped form a happy and memorable childhood with him, how we bonded over that sport.

We spent many afternoons during those first few years that I had moved home watching the Cubs lose a lot of games on summer afternoons, Lucy often lying on the floor next to one of us, raising her head off the ground in apparent concern at the noises we would bellow toward that box with the pictures and sound coming out of it before she would dismiss us, thump her tail on the floor, and drift back to slumber.

In that column, I wrote about the innocence of a father and his son, a boy and his dad, lost together on a makeshift baseball diamond during once forgotten summer afternoons.

I never really excelled at baseball, and my dad never pushed me in those days to be something I wasn’t. That was what made those moments together so enjoyable and fun.

I closed the column with a story of me making the winning catch at a little league game when I was 11 years old, and how I would never be quite certain who enjoyed that moment more: my father or me.

In those years that I spent back at home with my parents, I began to encompass that same sense with Lucy as the evidence of her consistent happiness and contentment was all over her movements and mannerisms. Which one of us was enjoying the moment more? I’ve always felt that if she was even half as happy with me as I was with her, then she had been truly blessed with a world of bliss.

I cried uncontrollably through much of the writing process of that column, trying to see the words appearing on the keyboard through tear-filled eyes.

Lucy laid nearby as I pounded out that column, her ever-calming presence guiding me through the process. And she would continue to be there for me, to comfort me in the difficult months that would follow, as I would heal by continuing to live life through her eyes as much as I was able.

It really is true that the only uncertainty left between my dad and me was who enjoyed that catch more. There was nothing left unsaid between us. He had seen me get sober and we had rekindled that spark of my childhood as we spent those final months and years together saying “so long.”

0 Comments